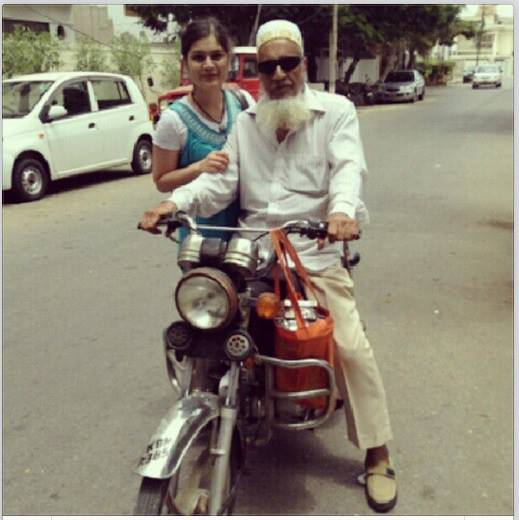

When people ask me what it was like to grow up in Karachi, one memory always comes first: my grandpa and I on his Vespa, weaving through the streets to pick up freshly made halwa puri on a Sunday morning. The breakfast dish consists of crispy fried bread, sweet halwa, and a chickpea and potato curry. I’d tiptoe into his room at dawn, shaking him awake, eager to convince him to go. But I never really had to—he’d never let us miss a weekend.

It’s been 20 years since we left Pakistan for Canada. My extended family no longer lives in the same house or even the same neighbourhood. My grandpa is gone now, too. But our family has also grown—new spouses, new kids. It’s funny how we subconsciously expect the world to pause for us, to stay the same until we return at our convenience. Nine-year-old me learned the hard way that it never does.

Nothing feels the same anymore when I go back—except the food. The food, for lack of a better word, slaps. Every bite of halwa puri takes me back to my grandpa. Every time I see a mango, I hear myself narrating, These aren’t as good as the ones dadaji used to bring home.

If you’re looking for lush forests, fresh air, or an escape from the daily grind, Karachi is not for you. Karachi is for those with thick skin and a thicker stomach. It’s chaotic, unpredictable, and relentless. But most of all, Karachi is where you’ll have the best street food of your life.

Feb 2025 was my first visit back in seven years—the longest I’ve ever stayed away. In that time, I’d earned a new degree, built a new life, and somehow acquired a whole husband.

As an unarguable burger (a slang term for someone overly Westernized in taste and lifestyle), my relationship with Pakistan has shifted over the years. I went from rolling my eyes at shalwar kameez and cringing at fobby accents in high school to loving Pakistani dramas and poetry in university. I hated being emotionally blackmailed into marriage at 21 but romanticized Pakistan’s mountainous landscapes in the summers I spent there. In short, my feelings towards the motherland are complicated.

You know what’s not complicated? The food. In just four short days, we ate our way through my childhood. Every meal was a reminder—of my grandpa, of family, of a simpler time.

Here are some dishes I got to share with my husband this time around:

Chaat, Pani Puri, and Rolls

On our first night, my sister and her husband took us to Flamingo, a bustling roadside restaurant in Boat Basin, one of Karachi’s famous food streets. My brother-in-law wasted no time ordering the best dishes on the menu. I’d been here before, but we always ate in the car while juggling flimsy plastic plates. This time, we sat outside, fully immersed in the chaotic symphony of honking rickshaws and sizzling grills.

We had their famous dahi chaat—a glorious mess of crispy fried bread, chickpeas, potatoes, tamarind chutney, and yoghurt—layered to perfection. We devoured pani puri (crisp hollow shells filled with spiced water that explode in your mouth), and garlic mayo chicken rolls, Karachi’s take on a handheld wrap. It was hands down one of the best chaats I’ve ever had. Mousa couldn’t stop talking about the rolls.

Nihari

When Mousa first met my family in Toronto, my mom made nihari. He said he loved it, and ever since, she has made it every time he visits.

The name nihari comes from the Arabic word Nahar, meaning day. Originally a winter breakfast dish, nihari is now eaten at all hours. It’s a slow-cooked beef stew rich with spices that’s simmered for hours until the meat is melt-in-your-mouth tender. It’s served with freshly baked tandoori naan, but the real stars are the special versions—nalli (bone marrow) nihari and maghaz (brain) nihari—a Karachi speciality.

Paan

I don’t know how to explain paan to someone who hasn’t grown up eating it. It’s not Instagram-friendly, and it doesn’t often win over first-timers, especially if you see it being made on the streets. But it’s a staple of every desi food journey.

A paan is a betel leaf stuffed with a mix of areca nut, slaked lime, catechu, gulkand (rose jam), fennel seeds, and spices. It is meant to be eaten after a meal as a digestive aid. You take a bite, chew, and wait as the flavours unfold—sweet, bitter, floral, and earthy, all at once. It’s messy. It stains your lips red. And somehow, that’s part of the charm.

Halwa Puri

By day four, our stomachs had reached their limit, but skipping halwa puri was not an option.

I was most excited for Mousa to try it. The moment he took his first bite of the crispy, golden puri dipped into warm chana (chickpea curry), I knew. Love at first bite.

Aloo Paratha

There was no room for aloo paratha after halwa puri, but we made space. Freshly rolled and fried on a scorching hot tawa, the buttery, flaky bread stuffed with spiced mashed potatoes called out to us from the same shop. It was impossible to resist.

Spicy Fries and Corn

After an afternoon of bargaining for costume jewellery and handcrafted shawls at Gulf Market in Clifton, we spotted a street vendor selling spicy fries and roasted corn. He was a man with a rickety table, a plastic tub of seasoning, and, quite possibly, unwashed hands.

I hesitated. But then, a childhood memory hit me—my mom buying me the same fries and corn after every dreaded doctor’s visit. Nostalgia won. We got a cup of each. It was worth it.

A Special Shoutout

To my aunt’s biryani, my other aunt’s haleem, and my dad’s endless side quests to end the night with a fresh glass of orange juice—thank you for making this trip taste like home.